Map of Sudan with archaeological sites of interest

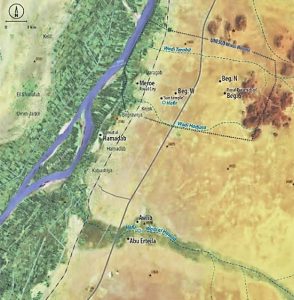

Area between Al-Dabba and Karima with archaeological sites of interest

DABBA DAM ARCHAEOLOGICAL SURVEY PROJECT (DDASP)

The Dabba Dam Archaeological Survey Project covers the area between Dabba and the Merowe Dam, upstream towards the 4th Cataract on the Nile. The primary aim of the project is to identify and document archaeological sites. To date over 200 sites, ranging from Prehistoric to 19th/20th century date, have been identified and some excavated as well.

KORTI (DS 128) – the modern village of Korti is located approximately 70 km upstream from Dabba. A Meroitic cemetery (approx. 18° 05′ 4.4″N, 31° 35′ 48″E) with over 20 graves located nearby has been partially excavated by the NCAM archaeological team.

MANSOURKOTTI (DS 2) – the modern village is located approximately 40 km upstream from Dabba and some 305km north of Khartoum. A Meroitic to Post-Meroitic date cemetery (18° 02′ 0.1″N, 31° 20′ 01″E) has been identified north of the village and approximately 250 m south of the Nile, covering an area of 460 m x 200 m. A total of 88 tumuli have been recorded; most of the inhumations were plundered in antiquity.

Burial site at Ousli East with modern settlement in the background. Photo: I. Kozieradzka-Ogunmakin

OUSLI EAST (DS 231) – the modern village is located approximately 15 km upstream from Korti and 40 km from the modern town of Karima. A Late Meroitic to Post-Meroitic cemetery (18° 12′ 10.8″N, 31° 41′ 5.7″E) identified as part of DDASP is currently endangered by a growing modern settlement. Archaeological excavations conducted in February 2018 aimed to document the location of the identified graves and recovery of several inhumations.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Fawzi Hassan Bakheit (2017). The Debba-Dam Archaeological Survey Project (DDASP). QSAP. Two seasons 2013-2014 and 2014-2015. Proceeding of the 1st International Conference for Bauyda Desert studies 2015. Münster.

Fawzi Hassan Bakheit (2016). Late Meroitic cemetery in Mansourkotti, Northern Sudan. Nyame Akuma 86: 80-86.

Fawzi Hassan Bakheit (2015). QSAP Dam-Debba Archaeological Survey Project (DDASP). Preliminary results of the second season. Sudan & Nubia 19: 149-160.

Mahmoud Suliman Bashir (2014). QSAP Dam-Debba Archaeological Survey Project (DDASP). Preliminary report on the NCAM mission first season, 2013-2014. Sudan & Nubia 18: 156-162.

EL-DETTI

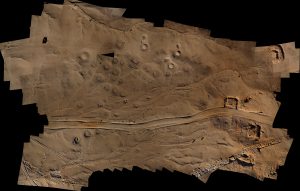

Aerial view of the site. Photo: S. Lenarczyk, A. Kamrowski

The modern village of El-Detti lies approximately 13 km downstream from the modern town of Karima and 7.5 km upstream from el-Zuma, between the royal cemetery at El-Kurru and a Christian site at Kajabi. The Post-Meroitic cemetery (18°25′27.41″N, 31°46′33.67″E) is located to the north-east of the village and its main part covers an area of approximately 500 m by 400 m. The largest group of tumuli (50 structures) is located in the southern part of the site, with some further burial structures identified approximately 300 m to the north-eats of the main cluster of burials. All tumuli investigated at the cemetery were plundered in antiquity. The modern constructions now endanger the site and seasonal water flow further contributes to the site’s gradual degradation.

Archaeological investigation of the El-Detti cemetery is part of the Early Makuria Research Project, conducted by a team from the Polish Centre of Mediterranean Archaeology, University of Warsaw, in collaboration with NCAM. It is a comprehensive research programme created to study a significant period in Nubian history — a period of transformation, cultural changes and social evolution that has long gone unrecognized by archaeologists and researchers alike. The main aim of the project is to examine archaeological remains of the period in question (4th – 7th centuries AD) originating from the area between the Third and Fourth Nile Cataracts. Prior to the inception of this project, few and limited works had been conducted on just a handful of sites in the region, e.g. Tanqasi (Shinnie 1953), Tabo (Jacquet-Gordon, Bonnet 1971–1972), Gebel Ghaddar, Hammur-Abbassiya (El-Tayeb 1994; 2003), Kassinger Bahri (Paner 1998: 115–132), and Gebel Kulgeili (Abdel Rahman, Kabashy 1999).

BIBLIOGRAPHY

El-Tayeb, M., Czyżewska-Zalewska, E. Kowarska, Z. and Lenarczyk, S. 2016. Early Makuria Research Project: Interim Report on the excavation at El-Detti in 2014 and 2015. Polish Archaeology in the Mediterranean 25: 403-430.

Iwaszczuk, U. 2016. Animals from tumili in El-Detti, Sudan. From bone remains to ritual. Polish Archaeology in the Mediterranean 25:431-446.

EL-KURRU

Royal Cemetery at El-Kurru. Photo: I. Kozieradzka-Ogunmakin

One of the royal cemeteries established during the Napatan Period (c. 700 – 300 BC), located on the right bank of the River Nile, approximately 13 km south from Gebel Barkal. The cemetery was excavated by George Reisner and the joint University of Harvard – Boston Museum of Fine Arts archaeological expedition in 1918-19. Most of the pyramids excavated by Reisner date to the early Kushite Period.

El-Kurru (18° 24′ 36″N, 31° 46′ 17″E) is the burial place of many of the earliest Napatan kings and queens, as well as four of the 25th Dynasty kings who conquered and ruled Egypt. More recently, archaeological work at the site has been resumed by the International Kurru Archaeological Project (IKAP) co-directed by Dr Geoff Emberling (University of Michigan), Dr Rachael J Dann (University of Copenhagen) and Professor Abbas Sidahmed Mohammed Ali (University of Dongola, Karima).

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Dann, R. J., Emberling, G. et al. 2016. El Kurru 2015-16. Preliminary Report. Sudan & Nubia: 20 35-49.

Emberling, G., Dann, R. J. et al. 2013. New Excavations at El Kurru: Beyond the Napatan Royal Cemetery. Sudan & Nubia 17: 42-60.

Emberling, G., Dann, R. J. et al. 2015. In a Royal Cemetery of Kush: Archaeological Investigations at El Kurru, Northern Sudan, 2014-15. Sudan & Nubia 19: 54-70

Reisner, G.A. 1920. Note on the Harvard-Boston Excavations at El-Kurruw and Barkal in 1918–1919. Journal of Egyptian Archaeology 6 (1): 61–64.

EL-ZUMA

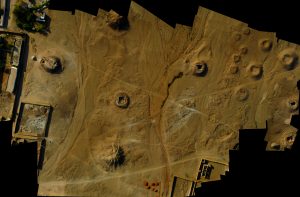

Aerial view of the cemetery. Photo: A. Kamrowski, S. Lenarczyk

El-Zuma is a modern village located approximately 6 km downstream from El-Kurru, on the right side of the Nile. The cemetery (18°22′09.69″N, 31°44′19.31″E) of the Early Makurian date – listed as a world cultural heritage site by UNESCO since 2003 – is located to the north of the village. The site has been known for nearly 200 years and has been investigated, but not excavated, by expeditions led by Richard Lepsius, Geaorge A. Reisner and Wallis Budge. Systematic excavations at El-Zuma began in 2004, led by Dr Mahmoud El-Tayeb, University of Warsaw, and Sudanese colleagues from NCAM. A total of 29 grave mounds identified on the ground surface represent three different types based on the construction and dimensions of the mound. All graves and their subterranean burial chambers were disturbed and looted but there is evidence, such as pottery, beads, metal fragments and animal bones, that they once contained burial equipment and funerary goods. Based on the pottery recovered from the burials, the graves are dated to the late 5th and early 6th centuries AD.

Archaeological investigation of the El-Zuma cemetery and other cemetery sites – El-Detti and Tanqasi – are part of the Early Makuria Research Project, conducted by a team from the Polish Centre of Mediterranean Archaeology, University of Warsaw in collaboration with NCAM.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

El-Tayeb, M., Skowrońska, E. and Czyżewska E. 2016. Early Makuria Research Project. The Results of Three Seasons of Excavations at El-Zuma Cemetery, 2013, 2014 ad 2015. Sudan & Nubia 20: 110–126.

Iwaszczuk, U., Niderla-Bielińska, J. and Ścieżyńska, A. 2019. Kings and peasants from El-Zuma/El-Detti microregion in the Early Makurian period. Economic aspects of animal bones from funerary contexts. PLoS ONE 14(2): e0212423. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0212423

Obłuski, A. 2005. Remarks on a Survey of the Tumuli Field at El-Zuma. Polish Archaeology in the Mediterranean 16: 400–403.

GABATI

A multiperiod site, discovered in 1993 by Michael Mallinson and Laurence Smith and excavated by the Sudan Archaeological Research Society team prior to the construction of a highway between el-Geili and Atbara. Human remains and artefacts recovered during the excavations are held at the British Museum, London, donated by the National Corporation for Antiquities and Museums in Khartoum, Sudan.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Edwards, D.N. 1998. Gabati: A Meroitic, Post-Meroitic and Medieval Cemetery in Central Sudan. Vol. 1. Sudan Archaeological Research Society Publication no. 3 London.

Edwards, D.N. and Rose P.J. 1997. The Meroitic, Post-Meroitic & Christian Cemetery at Gabati, Central Sudan, A Preliminary Report on the Excavations Of 1994/95. Kush 17, 69-84.

Judd, M.A. 2004. Gabati: Health in Transition. Sudan & Nubia 8: 84-89.

Judd, M.A. 2012. Gabati: A Meroitic, Post-Meroitic and Medieval Cemetery in Central Sudan. Vol. 2: The Physical Anthropology. Sudan Archaeological Research Society Publication no. 19 London.

HAMADAB

Geographical location of Hamadab (HamadabArchaeological Project)

The site of Domat al-Hamadab (16° 54′ 42″N, 33° 41′ 31″E) is located just 3 km south of the ancient capital city of Meroe, near the modern village of Hamadab. The site consists of two mounds, approximately 4m in height, which contain the remains of an ancient town and a contemporaneous burial ground. Archaeological research at Hamadab, led by Dr Pawel Wolf from the German Archaeological Institute, is focused on the town’s various architectural features with a special emphasis on the less spectacular but more significant domestic quarters to gain information on the daily life of its residents, their family organization, household activities, diet, and material culture. Recent research has contributed to the first complete map of a Meroitic urban settlement. This densely built town covers an area of approximately 200 m by 250 m and consists of two distinct part: a walled Upper Town in the north and unfortified suburban settlement to the south, the so-called Lower Town. The settlement had been inhabited from c. 300 BC to 400 AD. Based on the artefactual evidence, it could be assumed that the residents of the town were a community of non-subsistence specialists, commoners and their families, such as artisans, workmen, administrators, servants, guards and merchants.

For a virtual tour of the site visit the Hamadab 3D Project website.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Wolf, P. 2015. The Qatar-Sudan Archaeological Project – The Meroitic Town of Hamadab and the Palaeoenvironment of the Meroe Region. Sudan & Nubia 19: 115 – 131.

Wolf, P., Nowotnick, U. and Wöß, F. 2014. Meroitic Hamadab – a century after its discovery. Sudan & Nubia 18: 104 – 120.

Nowotnick, U., Wolf, P., Wöß, F., Büchner, S. And Minow, M. 2014. Hamadab: Urban living at the Nile in Meroitic times. DAI and QASP. Booklet intended for non-commercial use.

JEBEL MOYA

The site of Jebel Moya. Photo: Mike Brass

The Jebel Moya massif (13° 30′ 0″N, 33° 20′ 0″E) is situated in the relatively under-explored southern Gezira Plain in the Sudan, approximately 250 km south south-east of Khartoum and ca. 30 km west of Sennar. The massif has a perimeter of ca. 11 km. Its north-eastern valley was excavated by (later Sir) Henry Wellcome, the founder of the Wellcome Trust, over four field seasons from 1911 – 1914. Around a fifth of the estimated 10.4 hectares of the valley floor was excavated over four seasons, yielding a recorded 3135 human burials from 2791 graves. It is by far the largest and most intensively excavated cemetery anywhere in sub-Saharan Africa.

The archaeological and bioanthropological reports were published in 1949 and 1955 respectively (Addison 1949; Mukherjee et al. 1955). The vast majority of extant assemblages and the expedition records are curated at different institutions in the United Kingdom. The excavation cards and extant skeletal assemblages at the Duckworth Laboratory (University of Cambridge) together with a field diary from the second season’s field director, geological reports from the third and fourth seasons, a topographical survey map, Addison’s correspondences, plans of some of the burials excavated during the fourth and final season, cards describing artefacts and the photographic archive at the Griffiths Institute (Oxford) and the pottery samples at the British and Petrie Museums comprise the key materials curated in the United Kingdom. They have not been comprehensively re-evaluated, subsequent to the original reports, to determine the nature of social evolution at Jebel Moya.

Developments in archaeological inference and techniques provided a unique opportunity to re-orientate the published and extant material evidence within an updated interpretive framework on mortuary social organisation at Jebel Moya. This was accomplished by Brass’ (2016) doctoral research, which placed the site’s different phases of occupation in secure temporal contexts to allow for informed social analysis of change over time. In particular, it focused on questions of social organization and evaluates the nature of socio-political order in the southern Gezira Plain.

The current multidisciplinary project, led by Dr Michael Brass and Dr Ahmed Adam and funded by the Society for Libyan Studies, applies new approaches and collaborations to enrich our understanding of pastoral health, identity, mobility and economic pathways in arid and semi-arid environments from the Sudan and the Libyan Sahara approximately two millennia ago. Apart from building upon Brass’ previous research, it also draws upon pioneering work from the Italian-Libyan Archaeological Mission in the Acacus Mountains (Libyan Sahara), the Desert Migrations Project (Libyan Sahara), the Gobero Archaeological Project (Ténéré Desert, Niger), the Southern Methodist University/University of Khartoum Butana Archaeological Project (central and eastern Sudan), the Italian Archaeological Mission (central Sudan), the Czech Institute of Egyptology Mission at Jebel Sabaloka (central Sudan) and Hackner’s doctoral morphometric studies of Jebel Moya, Gabati (central Sudan), northern Sudanese and Upper Egyptian human remains. This project uses the vast mortuary and habitation site of Jebel Moya as a case study to examine how pastoral communities were constituted, inscribed their identities in the landscape and facilitated trade.

Outside of the immediate Western Desert of Egypt, there are few large excavated archaeological sites containing pastoralist components in the Sudan and the Libyan Sahara. As such, the results from this project’s re-excavation of Jebel Moya in October 2017 and, funding permitting, forthcoming in October 2019, will be placed in a broader context of botanical, isotopic, material culture and osteological studies from earlier pastoral sites in the Acacus Mountains (di Lernia and Tafuri 2013, Tafuri et al. 2006) and at Gobero (Sereno et al. 2008, Stojanowski and Knudson 2014, Stojanowski 2013), and, contemporary with Jebel Moya’s mortuary phase, the Garamantian civilisation in the Libyan Sahara, and the Meroitic-period occupation at Jebel Sabaloka (Suková and Cilek 2012) and Al Khiday (Usai et al. 2014) cemeteries (north and south of Khartoum). The material culture from the renewed Jebel Moya excavation and the material culture remains present in the National Museum in Khartoum (Sudan) will also be analysed to further test Brass’ (2015) hypothesis of trade contact between the southern Gezira and the contemporary Nilotic Meroitic state. In addition, the project also re-evaluates the hypothesis of Isabella Caneva (1991, Caneva and Marks 1990) of late Mesolithic connections between the Libyan Sahara and the southern Sudanic Nile Valley at the end of the late Mesolithic ca. 5000 BC.

The results from this project will thus not only significantly improve the chronological resolution of Jebel Moya and evaluate the existence and nature of social and trade networks with the southern Sudanic Nile Valley, but will also generate a unique bioarchaeological and socio-economic understanding of food production, gender, sex, health and social status in the wider eastern Sahara/Sahel two millennia ago.

SELECTED BIBLIOGRAPHY

Brass, M. 2014. The southern frontier of the Meroitic State: The view from Jebel Moya. African Archaeological Review 31: 425-445.

Brass, M. 2015. Interactions and pastoralism along the southern and southeastern frontiers of the Meroitic state, Sudan. Journal of World Prehistory 28: 1-34.

Brass, M. 2015. Mortuary theory, pottery and social complexity at Jebel Moya cemetery, south-central Sudan. In Kabacinski, J., Chlodnicki, M. and Kobusiewicz, M. (eds.) Hunter-gatherers and early food producing societies in Northeastern Africa, 414-440. Studies in African Archaeology 14. Poznan: Poznan Archaeological Museum.

Brass, M. 2016. Reinterpreting chronology and society at the mortuary complex of Jebel Moya (Sudan). Oxford: Cambridge Monographs in African Archaeology 92, Archaeopress.

Brass, M. 2015. Results from the re-investigation of Henry Wellcome’s 1911-14 excavations at Jebel Moya. Sudan & Nubia 19: 170-180.

Brass, M. and Schwenniger, J.-L. 2013. Jebel Moya (Sudan): New dates from a mortuary complex at the southern Meroitic frontier. Azania 48: 455-472.

Caneva, I. 1991. Jebel Moya revisited: A settlement of the 5th millennium BC in the middle Nile basin. Antiquity 65: 262-268.

Caneva, I. and Marks, A. 1990. More on the Shaqadud pottery: Evidence for Saharo-Nilotic connections during the 6th-4th Millennium B.C. Archeologie du Nil Moyen 4: 11-35.

Di Lernia, S. and Tafuri, M. A. 2013. Persistent deathplaces and mobile landmarks: The Holocene mortuary and isotopic record from Wadi Takarkori (SW Libya). Journal of Anthropological Archaeology 32: 1-15.

Nikita, E., Crivellaro, F., Stock, J., Foley, R. and Lahr, M. 2010. Human skeletal remains. The archaeology of Fazzan. Volume 3, Excavations of C.M. Daniels, p. 375-408. London: The Society for Libyan Studies.

Nikita, E.; Mattingly, D. & Mirazon Lahr, M. 2013. Late Holocene desert-induced stress and human migration through the Sahara: The case of the Garamantes. In Kotlia, B. (Ed.) Holocene: Perspectives, environmental dynamics and impact events, p. 219-259. New York: Nova Publishers.

Nikita, E., Siew, Y.Y., Stock, J., Mattingly, D., Lahr, M.M. 2011. Activity patterns in the Sahara Desert: An interpretation based on cross-sectional geometric properties. American Journal of Physical Anthropology 146: 423-434

Sereno, P., Garcea, E., Jousse, H., Stojanowski, C., Saliage, J.-F., Maga, A., Ide, O., Knudson, K., Mercuri, A., Stafford, T., Jr., Kaye, T., Giraudi, C., N’Siala, I., Cocca, E., Moots, H., Dutheil, D. and Stivers, J. P. 2008. Lakeside cemeteries in the Sahara: 5000 Years of Holocene population and environmental change. PLoS ONE 3: e2995.

Stojanowski, C. and Knudson, K. 2014. Human mobility responses to climatic deterioration and aridification in the Middle Holocene Southern Sahara. American Journal of Physical Anthropology 154:79-93.

Stojanowski, C. 2013. An archaeological perspective on the burial record at Gobero. In Garcea, E. (ed.) Gobero: The no return frontier. Archaeology and landsape at the Saharo-Sahelian borderland, p. 44-64. Frankfurt: Africa Magna Verlag.

Suková, L. and Cilek, V. 2012. The landscape and archaeology of Jebel Sabaloka and the Sixth Nile Cataract, Sudan. Interdisciplinaria Archaeologica Natural Sciences in Archaeology 3: 189-201.

Tafuri, M. A., Bentley, R., Manzi, G. and Di Lernia, S. 2006. Mobility and Kinship in the Prehistoric Sahara: Strontium Isotope Analysis of Holocene Human Skeletons from the Acacus Mts. (Southwestern Libya). Journal of Anthropological Archaeology 25: 390-402.

Usai, D., Salvatori, S., Jakob, T. and David, R. 2014. The Al Khiday cemetery in Central Sudan and its “Classic/Late Meroitic” Period graves. Journal of African Archaeology 12: 183-204.

TABO

An archaeological mound site located on the Argo Island on the Nile (19° 29′ 5″N, 30° 25′ 36″E), between Kerma and Dongola, excavated by the Joint Expedition of Henry M. Blackmer Foundation and University of Geneva (1968-1970). Uncovered on site was a well preserved temple of Amun; based on its measurements (75.6 m by 31 m), it is thought to be one of the largest Nubian temples. The temple is now heavily damaged due to the use of the stone blocks for building purposes by local inhabitants.

Archaeological excavations at Tabo continued until 1976 under the directorship of Charles Bonnet, University of Geneva, resulting in the discovery of burials dating to the Meroitic and Christian times.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Jacquet-Gordon, H. and Bonnet, C. 1972. Tomb of the Tanqasi culture at Tabo. Journal of the American Research Center in Egypt Vol. 9 (1971-1972): 77-83.

Jacquet-Gordon, H., Bonnet, C. and Jacquet, J. 1969. Pnubs and the Temple of Tabo on Argo Island. Journal of Egyptian Archaeology 55: 103–111.

Leclant, J.1975. Fouilles et travaux en Égypte at au Soudan, 1973-1974. Orientalia 44: 232-234.

Leclant, J.1973. Fouilles et travaux en Égypte at au Soudan, 1971-1972. Orientalia 42: 429-431.

Leclant, J.1970. Fouilles et travaux en Égypte at au Soudan, 1968-1969. Orientalia 39: 356-357.

Maystre C. 1974. La campagne de fouilles 1973-1974 du Centre d’études orientales. Université de Genève, Centre d’études orientales, Conférences 1973-1974, pp. 32–34.

Maystre C. 1973. La campagne de fouilles 1972-1973 du Centre d’études orientales. Université de Genève, Centre d’études orientales, Conférences 1972-1973, pp. 37–38.

Maystre C. 1972. La campagne de fouilles 1971-1972 du Centre d’études orientales. Université de Genève, Centre d’études orientales, Conférences 1971-1972, pp. 36.

Maystre C. 1971. La campagne de fouilles 1970-1971 du Centre d’études orientales. Université de Genève, Centre d’études orientales, Conférences 1970-1971, pp. 35.

Maystre C. 1970. La campagne 1969-1970 du Centre d’études orientales au Soudan. Kush 16: 23–25.

TANQASI

PCMA and NCAM excavations at Tanqasi, 2018. Photo: I. Kozieradzka-Ogunmakin

Tanqasi (18° 23′ 37.8″N, 31° 49′ 0.6″E) is a modern village located approximately 15 km downstream from Jebel Barkal on the southern bank of the Nile. The nearby Post-Meroitic cemetery features large tumuli, some measuring up to 36m in diameter.

The cemetery is currently excavated as part of the Early Makuria Research Project, led by Dr hab. Mahmoud El-Tayeb from the Polish Centre of Mediterranean Archaeology, University of Warsaw, in collaboration with Sudanese colleagues from NCAM. In 2018, the team excavated a total of five tumuli.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Klimaszewska-Drabot, E. 2010. Pottery assemblage from Tanqasi cemetery. Early Makuria Research Project (PCMA). In W. Godlewski and A. Łajtar (eds.), Between the Cataracts: proceedings of the 11th Conference for Nubian Studies, Warsaw University, 27 August – 2 September 2006, II.1. PAM Suplement Series 2.2/1: 219–226. Warsaw: Warsaw University Press.

Shinnie, P.L. 1954. Excavations at Tanqasi. Kush 2: 66-85.

Wyżgoł, M. and M. El-Tayeb. 2018. Early Makuria Research Project. Excavations at Tanqasi: First season in 2018. Polish Archaeology in the Mediterranean 27(1): 273–88.